Stories

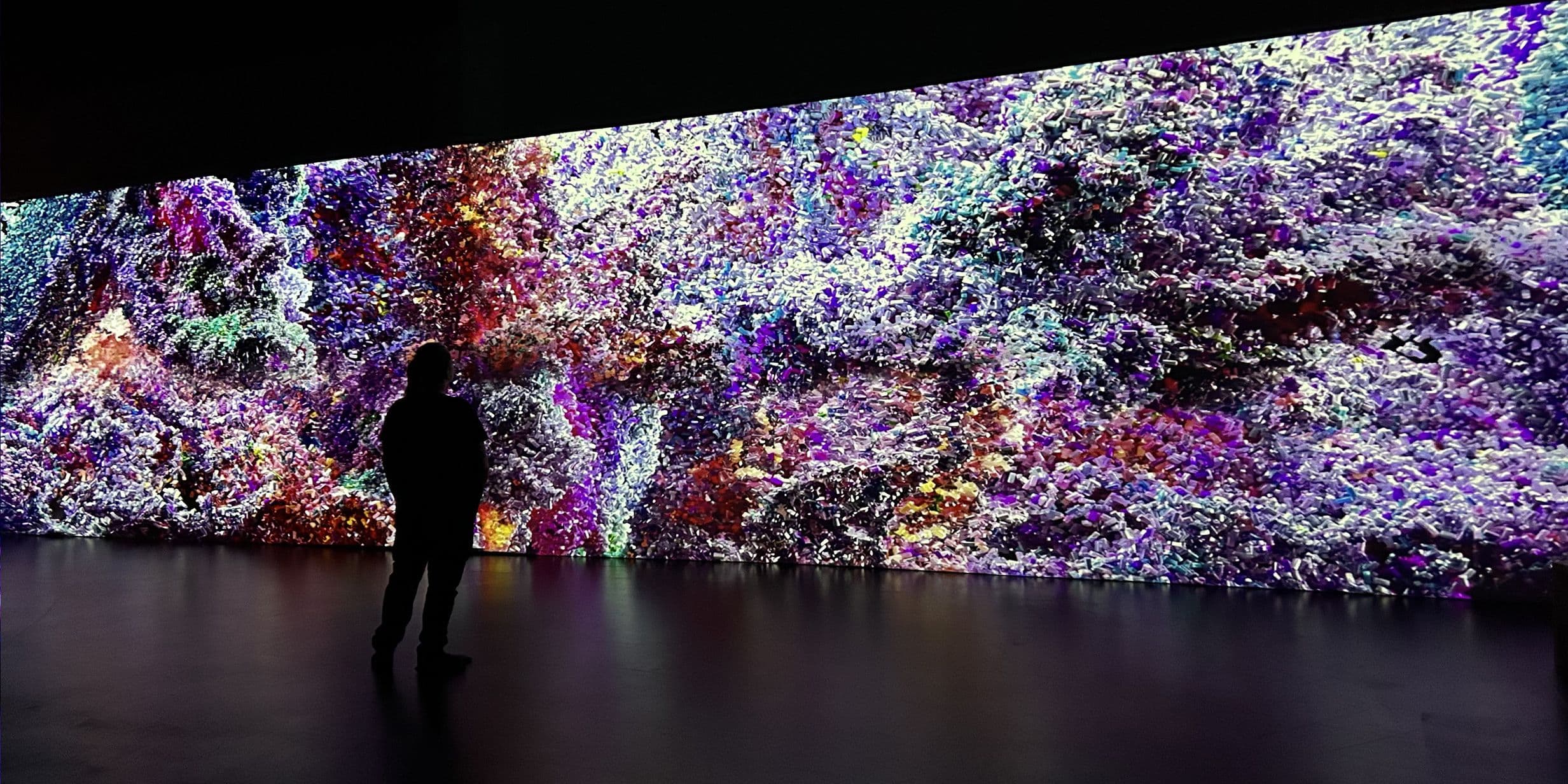

Memory Architects: the digital artist – Harry Yeff

How AI, sound and performance converge to question what we keep, what we lose and how our memories live on in digital form

Artikel overblik

Harry Yeff explores memory as something reconstructed – using AI, voice and performance to blur the boundary between human presence and data.

His work reframes sound as a lasting artefact – transforming voices into physical forms that honour identity, loss and emotional connection.

Through projects like Voice Gems, he reveals a growing desire for new rituals – ways to preserve, hold and meaningfully engage with memory in the digital age.